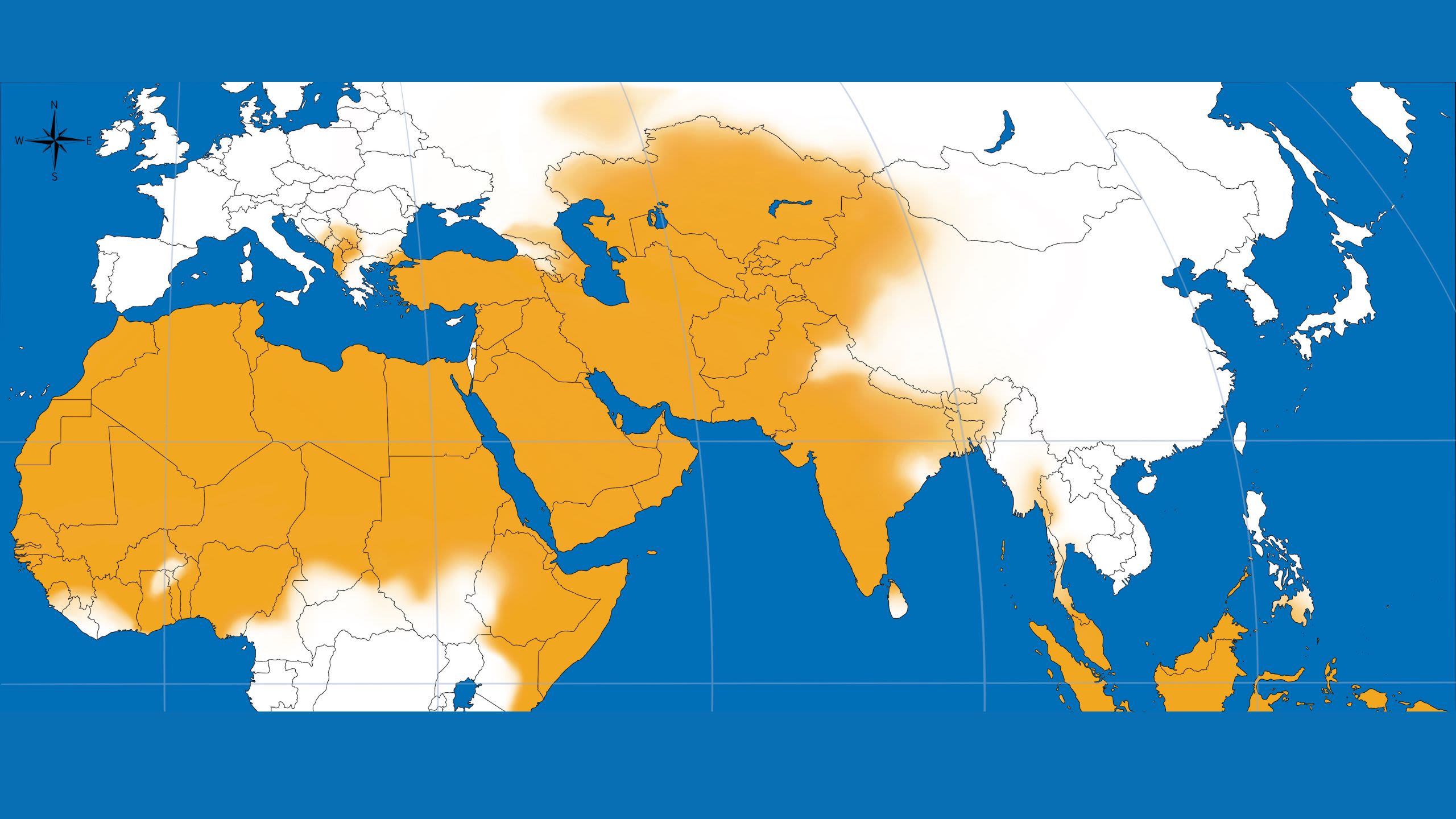

History of the Islamic World in 11 Maps

A Century of Islamic Expansion

750 CE

132/3 AH

The Muslim calendar starts in the year 622 CE when the prophet Muhammed emigrated from his native city of Mecca to Medina.

That is why the Muslim calendar is called Hijri, from the Arabic word Hijra, meaning “migration”.

The letters (AH) which follow dates in the Hijri calendar stand for Anno Hegirae ("In the Year of the Hijra" in Latin).

Lunar and solar calendars

There are over 40 different calendars in use around the world today.

Calendars are usually:

- solar (based on the time it takes the Earth to orbit the Sun)

- lunar (based on the cycles of the Moon's phases)

or a combination of the two (lunisolar).

The most widely used one — the Gregorian Calendar, called the Common Era (CE) — is solar.

The Hijri calendar is lunar

Each of the 12 months has 29 (or 30 days), which comes to 354 (or 355 days) in a year.

So the Hijri year is 11 days shorter than the 365/366-day year in the (solar) Common Era calendar.

Centres of Scientific Learning

850 CE

235/6 AH

During the 800s CE, about 200 years after the Hijra, Baghdad was the most important city in the Islamic World and a centre of scientific learning.

It was here that scholars of different faiths and cultural backgrounds worked together on topics — like mathematics and astronomy — that we now call science.

This elegant astrolabe — signed by one of the master craftsmen of the time — was made during this period.

Artistic Unity in the Islamic World

1000 CE

390/1 AH

In the year 1000 CE — about 400 years after the Hijra — the Islamic World stretched from Spain all the way to Iran.

Despite the huge distance, objects made in these lands shared very similar characteristics.

You can see these similarities in two of our astrolabes.

This one was made in Guadalajara (north of Madrid in Spain), around 1081/2 CE.

And this one was made in Isfahan (south of Tehran in modern-day Iran) between 984-1004 CE.

Size and layout: although at first glance they look like different designs, you can see that both these astrolabes share the same size and general layout.

Later European astrolabes were often more geometric in shape.

Star Map (rete): although the pointers use different styles, they are pointing to the same stars.

Find out more about astrolabes in Mirror of the Stars

Scientific and Artistic Achievements

1220 CE

616/7 AH

By the 1220s CE — as Genghis Khan’s Mongol army began invading from the east — craftsmanship in the Islamic World excelled both in engineering and the arts.

Made in Isfahan (in modern-day Iran) around 1221/22 CE, this astrolabe is the world’s oldest mechanical object still in working order.

It shows the phases of the moon,

and how the sun and the moon move relative to each other.

Watch how it works:

Made in the Egypt-Syria area around 1227/8 CE,

this astrolabe is engraved with beautiful images of the signs of the zodiac

and the Lunar Mansions (28 positions of the Moon relative to the zodiac as the Moon orbits the Earth in a lunar month).

The Influence of Islamic Culture

1300 CE

699/700 AH

For about 700 years, Muslim and Christian kingdoms lived alongside each other in Spain.

Jewish scholars and craftsmen also lived and worked in Spain during this time, leading to a fertile exchange of ideas, decorative techniques and technology.

And it was in Spain that the first European astrolabes were made, based on models from the Islamic World.

This astrolabe was made in Spain around 1300 CE.

Although it's inscribed in Latin, the star pointers and decorative “niches” on the bottom are very similar to the ones found on astrolabes inscribed in Arabic, like this example from Toledo in Spain:

Moving Frontiers

1453 CE

857/8 AH

Two conquests changed the frontiers of the Islamic World:

1453 CE: the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), which had been the capital of the Christian Byzantine Empire

1492 CE: the Christian reconquest of Islamic Spain (called the 'Reconquista'), led by Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella.

Because the Ottoman Empire was so close to Europe, there were fruitful exchanges between the two.

We think the Jewish astronomer Musa Jalinus made this singular spherical astrolabe around 1480/81 CE 884/5 AH.

He visited Venice from the Ottoman Empire.

New Centres of Craftsmanship

1550 CE

957/8 AH

With the foundation of the Mughal Empire in India during the 1500s CE, centres of power in the Islamic World moved east.

One of the largest workshops producing astronomical instruments in the Islamic World was in Lahore (in modern-day Pakistan).

For several generations it was run by the same family of craftsmen.

This beautiful astrolabe was made by Allah-dad, the founder of the workshop.

Working for the Rulers

1650 CE

1060/1 AH

Commissioned by Emperors and Shahs alike, astronomical instruments were highly sought after by the nobility.

Considered status symbols, their beauty was sometimes valued more than their usefulness.

This astrolabe was made around 1647/8 CE for the Persian Shah Abbas II.

You can see his name prominently inscribed on it. The beautiful calligraphic design on the rete (star map) reads: "Sultan Shah Abbas the Second."

This celestial globe was made in 1663/4 CE by a famous maker, Diya al-Din Muhammad, who worked for the Mughal Emperor.

Global Exchanges

1750 CE

1162/3 AH

By the 1700s CE, the Islamic World and Christian Europe regularly exchanged and traded objects.

Some items were produced in Europe specifically for export to the Islamic World, which meant they were inscribed in Arabic or Persian.

We think this dial may have been made in Europe, probably for export to the Ottoman or Persian market.

It's a marriage between a typical European sundial and a Persian qibla pointer.

European Colonisation

1880 CE

1297/8 AH

During the 1800s CE — when colonial powers dominated the Islamic World — many instruments made their way into European collections.

This qibla indicator — made in Persia during the 1800s CE — was part of a Belgian collection assembled during the 1900s CE.

It was then acquired by a British businessman and collector who donated it to our Museum in 1957 CE.

The Islamic World Today

Many of the historical scientific objects produced throughout the Islamic World are still made and used today – just in a different format.

Watches and clocks have replaced astrolabes.

And Qibla indicators – while still used to locate Mecca – are more often made of plastic or take the form of a smartphone app.

All maps are © History of Science Museum, University of Oxford

Curator: Dr Federica Gigante

Map artist and curator: Mathilde Daussy-Renaudin

Story design: Andrea Ruddock